Il Grande Ripensamento: addio al modernismo − e anche alla modernità (EN)

(Tratto dall’originale: [www].architectural-review.com/the-big-rethink-farewell-to-modernism-and-modernity-too/8625733.article - link alternativo: www.architectural-review.com/archive/campaigns/the-big-rethink/the-big-rethink-part-2-farewell-to-modernism-%e2%88%92-and-modernity-too ).

The second essay in the new Campaign decries Modernism for its betrayal of our essential humanity, and puts the case for why this must be regained to achieve true sustainability. In an emerging epoch based on a vision of a ‘living, organic universe’, architecture must start again to mediate our relations between nature, place and community.

Last month’s essay concluded by asserting that the ugent quest for sustainability spelt the end not only for Postmodernism, but also the termination of, rather than a return to, Modernism. If the former is not disposed to effective action (for reasons to be explored next month), the latter is unsustainable to its core. This month we start our investigation of the latter claim by exploring some key aspects of the unsustainability of modern architecture, recognising this belongs to the final, climactic phase of modernity − the era that started with the Renaissance and emergence of science. (The fundamental unsustainability of modernity, which further compounds that of modern architecture, will be explored in a later essay.) First, a caveat: although the downsides of modernity and postmodernity are a major topic of the Big Rethink, both cultural paradigms have also brought great and lasting gifts.

Not least of these are the vast amount of knowledge and potent technology modernity bequeaths us to use more wisely than it did. Indeed, both phases were very necessary and unavoidable parts of our socio-historic evolution. Despite now having to heal the fragmentation of our cities wrought by modern architecture, it too has brought its share of masterpieces and conceptual breakthroughs to be selectively carried forward; even Postmodernism has important lessons that should inform a future architecture. But both modernity and postmodernity are now played out, their benefits overshadowed by their negative aspects.

COMPARING AND CONTRASTING LE CORBUSIER’S VILLAS

To begin this investigation of modernity’s inherent unsustainability, let’s start by comparing a pre-modern work of architecture with a modern one. To add spice, let’s select houses by the same architect in different phases of his career: the Arts and Crafts (some would say proto-modern) Villa Fallet (1906-07) by Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, and the heroic, high modern and Purist (some would say, International Style) Villa Savoye (1928-31) by Le Corbusier, as he by then styled himself. The contrast is not as extreme as between, say, Heidegger’s Hut and Mies’ Farnsworth House, but is enough to make some key points.

Probably the most obvious contrast between the villas is in their forms: Villa Fallet is traditional and highly ornamented whereas Villa Savoye is abstract and stripped of decoration. But the next most striking difference is between the range and nature of materials. Typical of its time, Villa Fallet displays a broad palette of materials outside and in, many of them ‘natural’, and these have aged gracefully. Approaching and entering the house, these are encountered sequentially, according to contemporary notions of decorum.

By communicating how close you may come to them, they convey a hierarchy of public and intimate space, and also help articulate the character and relative importance of each room. The rough stone base outside forbids people getting too near; the smooth plaster in the entrance porch welcomes the body. Villa Savoye, by contrast, displays a limited range of materials, the same or very similar used inside and out, emphasising continuities of space and behaviour.

Designed in a gentler, more traditional Arts and Crafts idiom, Villa Fallet (1907) employs a broad palette of materials which have weathered gracefully overtime. A robust stone base roots the house to its site, while establishing a considerate relationship with its surroundings. Rooms are encountered sequentially, according to notions ofdecorum, and convey a legible hierarchy of public and more intimate domestic spaces. Architecture is conceived of as embedded in a rich and complex web of relationships

Imitating the smooth surfaces and forms of ocean liners, which similarly float free from context, these materials conceal the true nature of construction. With its plain surfaces and generous spaces, the house ‘hangs back’ from its inhabitants in a way that is liberating yet defies intimate engagement with its materiality. Attempting to stand outside time, the house neither aged nor weathered: it merely cracked and deteriorated.

Villa Fallet’s materials and forms act to differentiate. Together with an interior compartmentalised into rooms cluttered with furniture and decoration, they articulate the space through disjunction to constrain behaviour in accord with contemporary custom. But Villa Savoye’s sparsely-furnished, generously-scaled spaces emphasise continuities of material and spatial flow, and a concomitant exhilarating, fluid flexibility and freedom to the activities housed. Disencumbered of the clutter of heavy furniture and ornament, behaviour could be spontaneous and take on an epic quality, resonating as if played out against a blank cinema screen. Yet even here decorum is subtly indicated, for instance through private areas reached by turning clockwise against the anti-clockwise flow of the communal spaces, as well as the cruise-ship casual chic conveyed by the nautical associations, including ramp as gangway and so on.

Yet Villa Fallet’s interior discontinuities are reintegrated under the embrace of the roof, as its exterior forms, materials and ornaments suggestively imply multiple relationships with its setting. The heavy stone base draws up the earth and, with the transition to light, incised plaster above, speaks of gravity. So too does the steep overhanging roof that reaches up to the sky, its form suggesting the shedding of rain and snow as it snuggles against cold winds, while also opening up to the sun and views. And the decorative motifs of glazing bars, balustrades and incised plaster echo the surrounding conifers.

The house thus weds earth and sky while also establishing harmonious relationships with neighbouring homes and nature. Architecture was still conceived of as embedded in a rich and complex web of relationships − social, cultural, ecological and so on − and the materials and their use played a crucial role in communicating this concept. Time, too, was considered in the way the materials weathered and stained.

Villa Savoye is an antithesis, self-contained and selfish, a singular object hovering above but not engaging with its setting, its pristine forms denying and so vulnerable to weathering and time. It opens up only to the sun and sky while the horizontal slot, partly glazed and partly unglazed, both distances and intensifies the view of the horizon. The fluid interior-exterior space is bounded within the box-like perimeter that floats free above the ground to emphasise the disconnection from context and nature. Indeed, the building appears to stand on tiptoe, recoiling from nature, like those old cartoons of women on chairs shrieking ‘Eeek!’ on seeing a mouse.

The fluid space of Villa Savoye (1931) is bounded by a box-like enclosure that emphasises the dwelling’s sundering from nature and place. Like many key modern houses, it is an isolated holiday home on a rural site, dependent on fossil fuels to make its materially insubstantial architecture habitable, and also to make possible the regular weekend commutes of itsoccupants. This egotistical sense of hubristic disconnection, of humans prevailing over nature, has consistently underscored the modern era.

On entering, the first thing encountered is a wash-hand basin at which to quickly remove any of nature’s contaminating dirt. This was, of course, only a brief phase in Le Corbusier’s oeuvre, and the post-Second World War houses, such as Maisons Jaoul, are earthy and earth-bound. The attitude displayed to contamination is nothing like as extreme as with the sterile and joyless paranoia of Alison and Peter Smithson’s 1956 House of the Future, as described in last month’s review of the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s exhibition Imperfect Health: the Medicalization of Architecture (AR January 2012). The naval forms emphasise this floating disconnect − although, this being a Corbusian masterpiece, there are also allusions to Palladio’s Villa Rotunda, its dome fragmented into a Cubist collage of curved walls, and the statues of gods on the entablature replaced by a live frieze of humans, of elevated status of course, framed by the near continuous horizontal slot.

TAKING THE LONG VIEW OF ‘THE OIL INTERVAL’

So what accounts for the differences between these villas? Specifically, what new material facilitated the profound shift in forms and sensibility? What do the history books say? Reinforced concrete? Plate glass? The answer is neither of these, nor any of the other usual explanations, but abundant and cheap fossil fuels. These powered the weekend commute to the house and kept warm in winter the large, flowing spaces enclosed in thin un-insulated concrete walls and slabs, with vast expanses of single glazing. It was also a related material − and later, oil derivatives − which waterproofed Villa Savoye’s and all other flat roofs and terraces. Later too, petrochemicals provided the neoprene gaskets, epoxies, mastics and sealants, as well as the synthetic carpets and fabrics.

And it was fossil fuel-derived electricity that lit and air-conditioned modern buildings, which often spurned natural light and ventilation. Modern architecture is thus an energy-profligate, petrochemical architecture, only possible when fossil fuels are abundant and affordable. Like the sprawling cities it spawned, it belongs to that waning era historians are already calling ‘the oil interval’. Although histories of modern architecture still overlook this critical fact − failing to note what is, literally, blindingly obvious − any future history must surely begin by noting this relationship, which is axiomatically unsustainable.

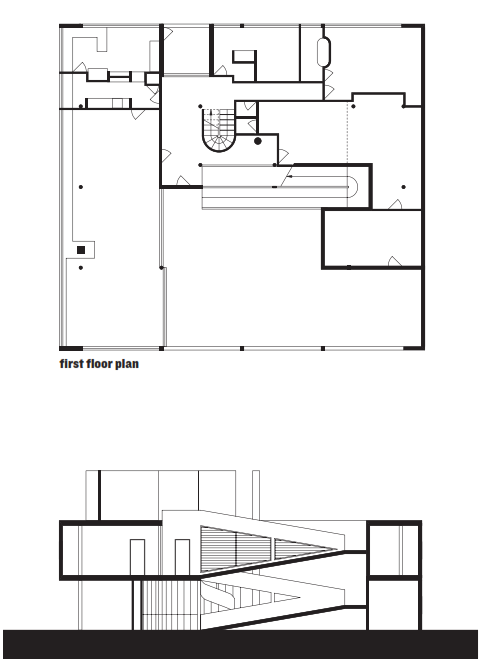

Ground floor plan of the Villa Fallet (1907).

With its disconnect from nature and neighbours, its material fragility and the frieze of people partying or doing calisthenics displacing the statues of gods on the classical entablature, Villa Savoye emphasises a related flaw at the core of modern architecture and modernity in general: the hubris, turbocharged by fossil-fuelled technological power, and a corresponding lack of acknowledgement, even denial, of our ultimate dependency on nature, its cycles and regenerative capacities. Archetypal modern man and woman preferred − and still prefer − not to be rooted in place or community nor to be concerned with the longer cycles of time and the obligations they inevitably incur.

The modern and contemporary built environment, and their corresponding lifestyles, are only possible because we do not live within the capacities of the Earth’s ambient energies and nature’s annual bounty but instead each year burn up a legacy accumulated over millions of years. As the title of Thom Hartmann’s famous book so poetically puts it, we are living on ‘The Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight’. Yet already as a student in the 1960s, I was aware of Buckminster Fuller’s injunction that we recognise fossil fuels as a ‘one-time evolutionary gift’, the only legitimate use for which was to create the means to harvest what we now call renewable energies.

Even the food we eat is the product of oil rather than nature. Very many times more oil-derived calories are used to produce and distribute it − in artificial fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides, tractor and transport fuel, plastic packaging and refrigeration − than it yields nutritionally, only one of many ways modern agriculture is utterly unsustainable. Adapting food provision to escalating oil prices will lead to immense challenges − and inevitably to profound changes in how we live on and with the land.

GETTING TO THE ROOT OF THE PROBLEM: MOBILITY

The hubristic disconnect and denial of dependencies is clearly summarised by Villa Savoye. Modern mankind has been said to be merely picnicking or camping upon the Earth, thereby escaping what were seen to be the constraints of custom, culture and community − neither properly settling, nor even taking away the rubbish − most of it created unnecessarily (all that packaging and so on) and all of it treated as an ‘externality’ for others to deal with.

It is little coincidence that many famous modern houses were isolated holiday homes − Villa Savoye, Fallingwater, Farnsworth House − and many of the buildings in FRS Yorke’s canonical ‘The Modern House’ (AR December 1936) are also holiday homes. Like their more famous counterparts, many of these perch on stilts or cantilever over their sites.

Inside the modern house, the light, mobile modern furniture derives from that used on holidays − deck chairs and other folding equipment. These in turn were derived from the furniture used by the military and later by colonial administrators on safari. Military conquest through technological superiority and colonialism were further hubris-inducing enterprises that inspired aspects of modern architecture and design, largely initiated by colonial powers − France, Britain, Germany, the Netherlands. And from the colonised came many aspects of modern life, such as lighter and less constrictive clothing befitting the more spontaneous and relaxed lifestyle seen as concomitant with modern architecture. Recognising modern architecture’s antecedents in colonialism and conquest raises questions about how benign or psychologically healthy is the tendency to merely camp without establishing deep roots.

Mobility and modernity are virtually synonymous. Particularly in the UK and US, a house is not a home but an investment and stepping stone until something better can be afforded. But can we achieve sustainability without being settled? Without treating our setting, the surrounding bioregion and its climate, customs and agricultural produce, and even the planet and its biosphere as home? Without being rooted in place and responsible for the stewardship of that place? These are pressing questions to ponder when rethinking architecture and the city, our lifestyles and cultures. An equally important and related question is: can we be fully mature humans without being settled?

East elevation of the Villa Fallet, Le Corbusier (1907).

A modern ideal was to be ‘a man or woman of the world’, always on the move and at home everywhere. But now we see universality, the unfolding into full humanity, as being achieved through depth, which comes in part from being rooted in and concerned for place and community. Partly inspired by Villa Savoye and other holiday houses, as well as holiday pursuits such as camping and yachting, there still persists a long-enduring and now pernicious myth in architecture − found at its most pathological in High-Tech, to which a few architects cling nostalgically − that a light, and preferably hovering, building is more gentle in its impacts on nature and its setting. This was excusable in the days when Buckminster Fuller, who defined his mission as using minimal material to bring maximum benefit to the majority, famously asked: ‘Madam, how much does your house weigh?’ But to ask the same question today about a Norman Foster building, as in the title of a recent documentary film, is simply silly.

INTEGRATING ‘EXTERNALITIES’ INTO ARCHITECTURAL THINKING

Total life-cycle costing, a key discipline in sustainable design, requires that we understand efficiency and ecological impacts in a very different way to modernity. This dismissed much of its negative impacts (particularly those of industry and corporations) as mere externalities or collateral damage.

Now we understand that what is critical is not the efficiency, lightness and strength of a material or component when in place: it is the total amount of material extracted from the Earth and the disruption caused by this, as well as the energy and pollution from transport and manufacture, and then the costs and impacts of eventual recycling or return to the Earth. Thus what were once seen as highly efficient high-tech materials or components are now seen to be very inefficient − indeed, with building, it is almost the rule that the more efficient the product when in place, the less efficient it is in process terms. For real efficiency, as the concept is now understood, nothing can beat mud and thatch, although Walter Segal’s timber self-build system scores highly as do traditional tropical construction techniques in materials, such as bamboo and palm-frond matting − which might be lightweight but are natural, local and renewable.

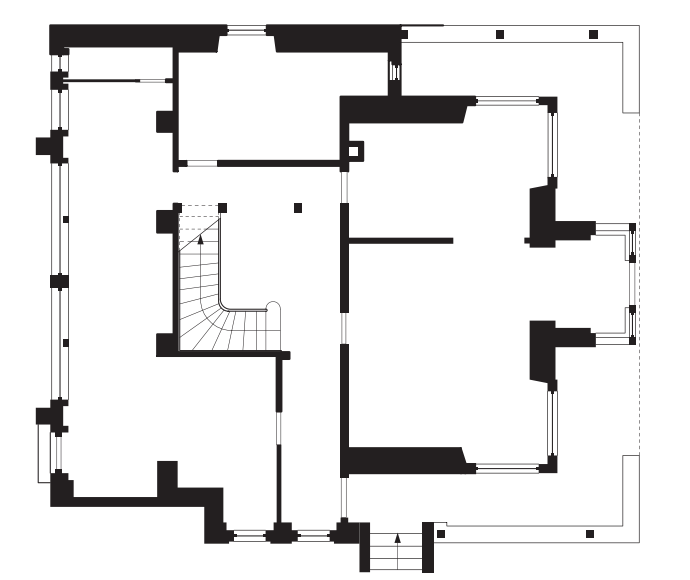

Section through the Villa Fallet, Le Corbusier (1907).

Design for sustainability will thus inevitably be centred on the shaping of processes, such as flows of material and energy, as much as on the eventual products. This requires vastly expanding the temporal and spatial range of the designers’ concerns to include the total life-cycle costs mentioned above, which would typically span decades, and the global impacts of, say, using a material in short supply, which might have profound consequences on the other side of the planet.

What are now dismissed as mere externalities for others, usually the taxpayers, to deal with, must now all be factored into the design process. Miniaturisation and ephemerality can be very destructive, as evidenced by the horrendous and too little publicised consequences of mining for rare earth metals used in computers, cell phones (of which Americans discard 130 million a year) and other electronic equipment, such as that used in monitoring and adjusting conditions within buildings.

All this will profoundly influence the design and making of architecture. And just as green design has already elevated the status of the services engineer as a key creative member of the design team, so too will it lead to the inclusion, as another key creative discipline, of production engineers, who are devising more efficient and benign ways of manufacturing materials and components.

Particularly important is to devise less energy-intensive and toxically-polluting methods of manufacture − hence the importance of biomimicry’s study of how nature creates high-performance materials, such as spider webs, at low temperatures with no pollution. It is a tragic paradox that modern architecture − which originated in buildings like Villa Savoye that promised a new, more healthy life of sun and fresh air in conditions of near-sterile cleanliness − should lead to buildings whose interiors are so poisonously unhealthy, with highly toxic off-gassing and abraded chemicals, as well as tinted glass and artificial light that inhibit the synthesis of Vitamin D and consequently cause a rise in its deficiency-related diseases.

CONNECTING WITH THE LARGER REALITIES OF AN ESSENTIAL HUMANITY

The indigenous peoples of North America, when confronted with major decisions, would ask: what will be the impact of the action under consideration on the next seven generations, as well as on the legacy of the seven previous generations? Like many pre-modern peoples they viewed their lives and actions within a vastly greater time span than the short-termism that dominates today’s business and political electoral cycles, and were acutely sensitive to the consequences of these for ancestors, descendants and Mother Earth. This is the true role of culture, to shape and keep alive the narratives and rituals that connect us to our place and peoples, to the planet and the long march of history and time, so giving meaning to and guiding our lives.

But modernity suppressed this dimension of culture, while modern architecture attempted to break with history and its outworn rhetorical forms and motifs. Stripped of obvious historic associations, Villa Savoye’s allusions to a classical past were only there for a select few, those whom Le Corbusier referred to as having ‘eyes that see’. Otherwise, the villa is a ‘machine for living in’, a compliant gadget in service to a hedonistic, live-for-the-moment lifestyle. In utter contrast, a pre-modern building is a cultural artefact, repeating and reworking forms loaded with historic significance so as to connect us with history while also addressing the future. Such architecture is not merely subservient, but mediates between us and both culture and nature, and so roots us within these contexts.

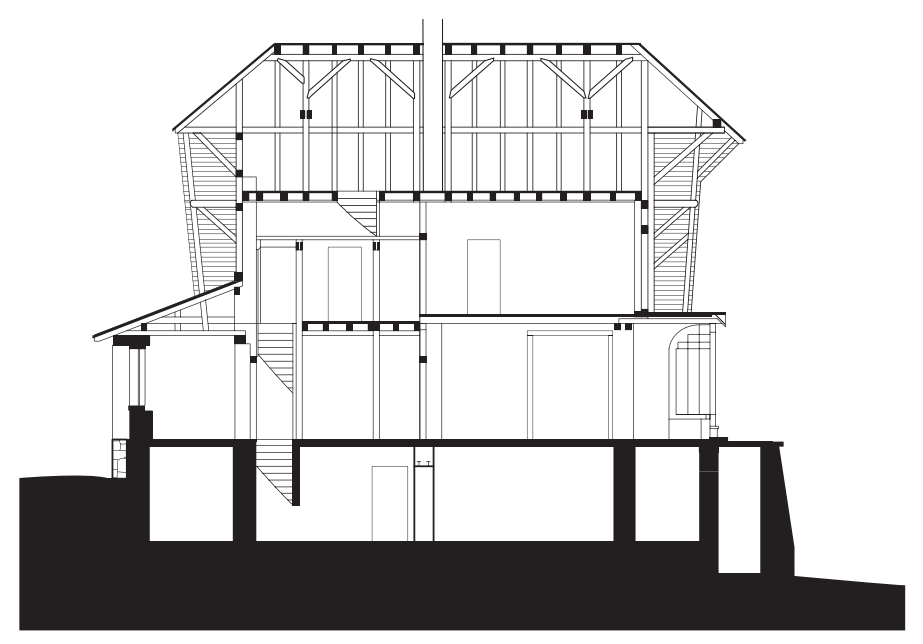

First floor plan and section of the Villa Savoye, Le Corbuiser (1931).

We cannot achieve sustainability without re-establishing this multi-dimensional sense of connection to and relationship with larger realities,

and the meanings and deep psychic satisfactions that this brings. In this light, it is significant that two forms of psychotherapy with rapidly expanding followings are ecopsychology, which attributes much mental malaise to our culture’s pervasive and increasing disconnect

from nature, and Bert Hellinger’s Family Constellations, a type of group therapy that powerfully revivifies, by bringing into consciousness, our profound and too often unacknowledged connections to our ancestors.

The rebirth of culture is among the greatest and most exciting projects of our age, a collaborative enterprise that will take time and the contributions of many. But contrary to what many say − particularly Postmodernists − the great, inspiring, and even spiritual, narratives are already there to be used as a foundation. They are to be found in, among other things, the cosmological unfolding that relates us back to the original fire ball of the Big Bang, in evolution and ecology that connects us with all other living things, to anthropology and depth psychology that tell us about the cultural and community connections that help us unfold into full humanity.

REGAINING THE HUMANITY BETRAYED BY MODERNITY

These narratives and the deep scientifically-based understandings underpinning them are among the greatest legacies of modernity. Yet they are also among the most potent agents undermining the reductionist assumptions on which modernity is founded. More than that, the knowledge and wisdom they bring, as well as the psycho-physiological techniques (from various forms of therapy, Neuro Linguistic Programming and so on) that have emerged to reconnect us with others and the larger world while healing what is pathological in those connections, face us with a challenging responsibility.

That is nothing less than to apply the gifts bequeathed by modernity to, for the first time, consciously participate − not by imposing our will, but by working in harmony with what these narratives reveal − in shaping our destiny to bring about a sustainable society and environment. And these will be sustainable not least because the concomitant cultures and lifestyles will offer the deep psychic satisfactions of a meaningful life − rich in connections to nature, place and community, and the responsibilities that go with those − in which we can each mature into and express our full humanity.

Ultimately this series is concerned with returning the human subject − and his or her unfolding into the fullness of humanity in line with emerging understandings of what that means − to its correct and central role in architecture after being displaced from there by reductionist ideas like Functionalism. This was concerned only with activities as viewed detachedly from outside, and ignored our rich internal worlds of experience, psychic connections and meanings. Put in these terms, modern architecture was a huge betrayal of our essential humanity − an extreme statement that is not without much truth.

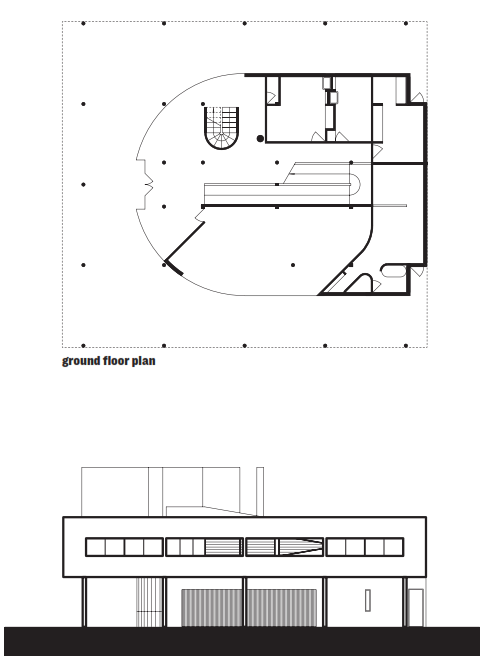

Elevation and ground floor plan of the Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier (1931)

But before exploring such matters further and discussing what they mean for the future of architecture, we need to understand where we are historically and the deep, seldom-discussed, forces that brought us here (next month’s subject), as well as those now impelling us to move forward by bringing modernity to an end. We shall touch on the latter first and briefly summarise a few of the most potent of these forces that are also opening a new era in which ideas such as regenerating culture will be recognised as relevant and realisable.

These are mostly, or could be usefully seen as, the ‘carrots’ that complement last month’s ‘sticks’, although some of them are exactly the same forces. Focusing on ‘quality of life’, not ‘standard of living’ The environmental crisis, for instance, is most definitely

a ‘stick’ that should be, but is not, impelling urgent action. In part that is because the crisis has not been understood to also be a ‘carrot’; or if it has, environmental activists mainly focus on the ‘stick’ aspect − for good, if counter-productive, reasons. But within the threat of catastrophe also lies opportunity, not least because people become more open-minded when they realise that radical thinking and action are required urgently.

As the study of biological evolution, history and psychology makes clear, major crises (what biology and systems thinking call bifurcation points) lead to either breakdown or break through. We are currently poised between these options, frozen like rabbits in car headlamps when confronted by the enormity of the environmental problems we face and the seeming intractability of mobilising effective action − and some still even deny there is a problem. The challenge we face is to make a huge evolutionary step forward to a very different cultural paradigm (or cultural ecology, as some prefer) beyond modernity.

The best answer to climate change deniers and sceptics is that if the threat it poses proved unfounded it would be both a relief and a disappointment. We would be losing the impetus to make a huge evolutionary leap. Here the rhetoric and actions of many environmentalists are counter-productive, for two reasons in particular. Many tend to be preoccupied by single issues, often seeing these as related to one cause, and propose single solutions. Such thinking is profoundly un-ecological: ecology is concerned with complex, interacting webs of relationships, not straight-line cause and effect.

Maybe even more problematic, environmentalists have a habit of articulating only the problems, real and pressing as they are, and advocate constraints, such as limiting energy-consumption and emissions. Although these constraints are necessary, to focus exclusively on them and the problems they ameliorate is disempowering and dispiriting. Instead, or as well as, we need to be inspired by a vision of what is possible, of what might go along with cuts in consumption and emissions: the leap to a saner and more satisfying culture based on the switch from a focus on standard of living to quality of life. (Seeing the latter two as synonymous was a major flaw of modernity.) Quality of life is a product not of isolation and disconnect but of enjoying the beauty and grace, the satisfactions and meanings of living in deeply aware connection with place and community, nature and planet.

‘MODERN ARCHITECTURE IS AN ENERGY-PROFLIGATE, PETROCHEMICAL ARCHITECTURE, ONLY POSSIBLE WHEN FOSSIL FUELS ARE ABUNDANT AND AFFORDABLE. LIKE THE SPRAWLING CITIES IT SPAWNED, IT BELONGS TO THAT WANING ERA HISTORIANS ARE ALREADY CALLING “THE OIL INTERVAL”.’

Many studies show that a higher standard of living (above a baseline necessary for dignified life) has not brought happiness, and also that quality of life is not dependent on excessive consumption. Among the great problems of our time, especially in relation to environmental and economic problems, is a desperate lack of creative imagination in conceiving of and articulating a pragmatic yet inspiring alternative vision as to what the good life would be. As well as a certain standard of living and long-term security, this would bring deep happiness and satisfactions through connection and communion with all aspects and forms of life, and a deep sense of purpose.

Meeting this exciting challenge is fundamental to achieving sustainability and why we need to see the environmental crisis as a carrot as well as a stick. Green buildings alone improve the quality of life. People prefer working in naturally lit and ventilated buildings, as evidenced in lower staff turnover and less absenteeism, the latter in part because green buildings are healthier. People also prefer controlling their own comfort conditions, as operable windows allow.

Researchers have found many workers happy with conditions considered outside normal comfort zones − if they chose and control these conditions. Also, many features introduced for energy-efficiency, such as naturally lit and ventilated atria, become lively social spaces and give a building a pleasing and recognisable identity. Moreover, green buildings do not exhale hot air from chillers and other mechanical equipment, and especially if they also have planted roofs, contribute markedly less to the urban heat-island effect. But these are only small steps in what must become a broader, city- and culture-wide transformation in which architects should play a leading role. Closely related to the environmental crisis is the economic one that can also be seen as a carrot.

Like modernity, many aspects of the current economic system are played out and need more than mere reform. They are the prime drivers of the destruction of the planet and their benefits are unequally distributed, grotesquely enriching a tiny elite and leaving a large minority in conditions of relative deprivation. Now the economic underpinnings of modernity are under threat and even collapsing, for reasons we shall explore shortly.

At the moment, in the developing world we are in a transitional phase that has had its architectural consequences. In A Whole New Mind, Daniel Pink argues that in Europe and America we are leaving the Industrial and Information Ages to enter the Conceptual Age. Our Industrial Age ended as factories moved to exploit the cheap yet skilled labour of the developing world, leaving empty industrial areas to be redeveloped as housing and business parks − and some old factories, power stations and other industrial works converted into galleries, theatres, concert halls and so on. But if moving manual factory labour to the developing world helped bring the Information Age, the equally rote and nearly as drudge-like aspects of this are now also moving to the developing world: call centres, accounts, archives, records and simple software development − even legal advice and medical diagnostics.

All these require linear, left-brain skills. This leaves the developed world to concentrate, until the developing world catches up again, on the right-brain, high empathy skills and pursuits of the Conceptual Age, notably those involving creativity, culture and caring. A well-educated, long-lived post-retirement population appreciates the stimulus of culture, yet also requires caring for − often by recruits from the developing world. In the globalised, Conceptual Age, cities rather than countries compete to attract the creative and highly skilled people on which their economies depend. Contributing to success here is quality of life, to which the socio-cultural and physical character of a city and its hinterland are also crucial factors.

THE ‘CONCEPTUAL AGE’ AND THE ‘THIRD INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION’

The advent of the Conceptual Age, with its emphasis on empathy and creativity, could be seen as a step towards a much more important transformation, what Jeremy Rifkin, in his book of the same name (see book review on page 97), calls the Third Industrial Revolution (TIR). Each industrial revolution is characterised by the confluence of a new energy system with a new mode of communication, these being analogous to the body’s blood and nervous systems. The First Industrial Revolution used steam power for manufacturing and transport (the railways), and for mass-printing rotary presses. The Second Industrial Revolution (SIR) used oil to power transport (roads and motorways) and electricity − from coal- and oil-fired power stations (later some nuclear) − for industry and communications, from telegraph and telephone through to cinema and newsreels to television and faxes.

The blue- and then white-collar jobs of the First and Second Industrial Revolutions involved largely rote, drudgework and huge inequalities between boardrooms, managers and ordinary workers in pay, education, healthcare and so on. Both revolutions required massive investment in machinery and infrastructure. Financing this led to centralisation and the consolidation of power in a limited number of mighty corporations and financial institutions. This investment was also heavily subsidised in various ways, from tax breaks to publicly-funded infrastructure, by the government and taxpayer.

This is now all too often dishonestly denied by corporations and politicians decrying big government, over which business and banks nevertheless retain huge influence through lobbying and political donations. Indeed, the current economic crisis was largely caused by pushing this now deregulated (part of the denial of the government’s role) SIR beyond any sensible limit and simultaneously obstructing the transition to TIR through lobbying and funding various spoiling actions. (Climate change deniers, opponents of renewable energy and so on are funded by the oil and nuclear lobbies.) TIR − which the European Union was strongly committed to bringing about, before being distracted by the need to rescue some of its individual, debt-ridden economies − is very different. Energy is from distributed, ubiquitous renewable sources, with every building a micro power station, and the communication system is the internet.

These will come together, using available and tested technologies, in what has been called the Smart Grid, which moves energy and information in both directions. Instead of centralisation it leads to a dispersal of power and instead of competition between a few, often near-monopolistic, corporations it leads to collaboration between a myriad of small businesses and individuals. And rather than living on the hubris-inducing powers of fossil fuels and wantonly extractive industrial processes, we will be living in harmony with the biosphere and its ambient energies.

This must lead to greater awareness of them, their capacities and limits, and so to a more meaningful and improved quality of life. The implications of all this for the built environment are enormous − as they are for all aspects of our culture, requiring the radical thinking of economics and education, for starters. Perhaps surprisingly, particularly to advocates of the Compact City, TIR may yet rescue the environmental legacy of the Second Industrial Revolution.

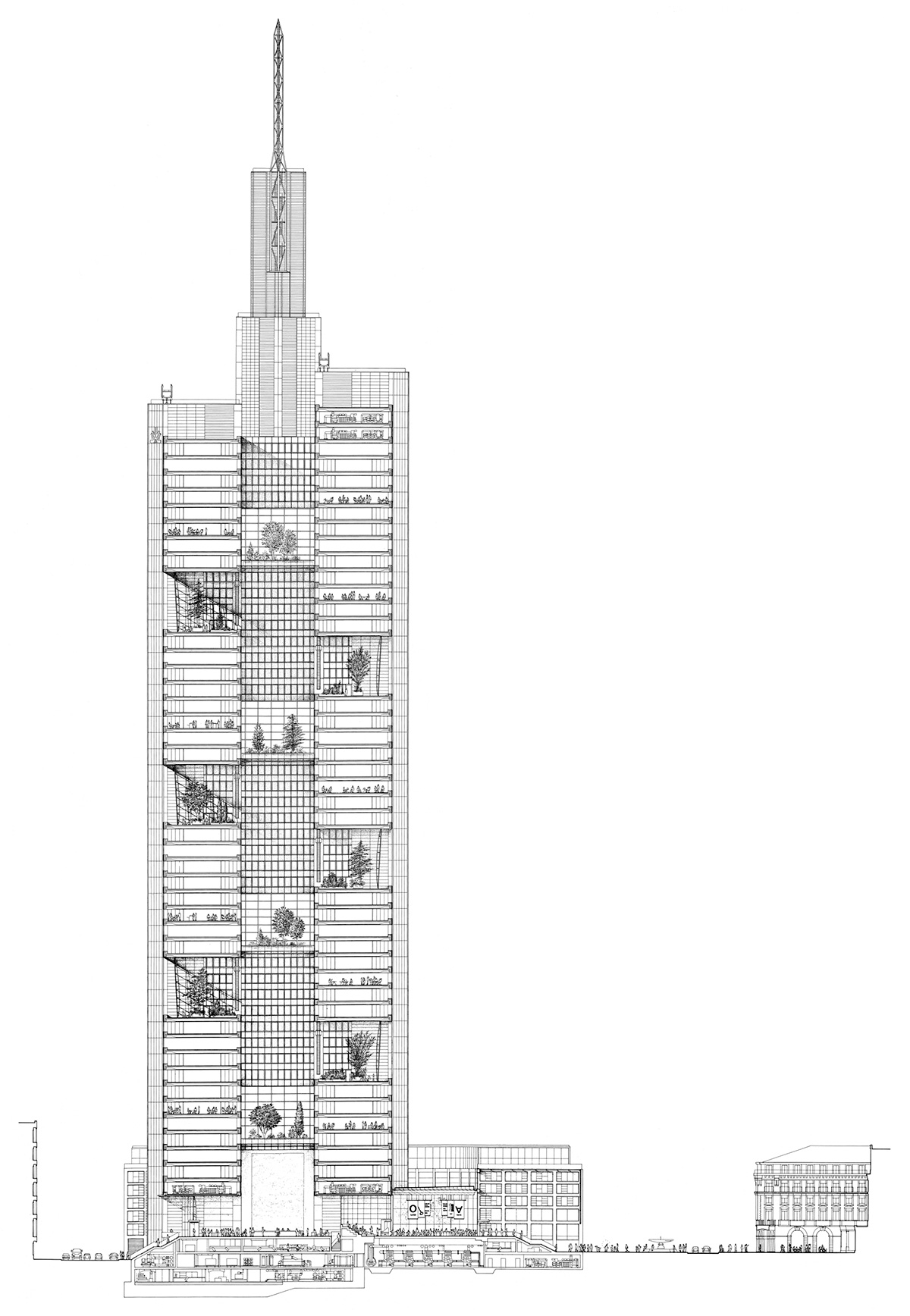

Section through the Commerzbank Tower in Frankfurt by Foster + Partners showing the sky gardens dispersed throughout the structure. These allow more natural light to penetrate the interior, reducing the need for artificial sourcesand cultivating a general sense of well being. Despite its scale, Commerzbank was one ofthe first genuinely ‘ecological’ skyscrapers.

To fly over the US, to take an extreme example, is to wonder how its lifestyle, with multi-lane highways filled with cars of single occupancy, commuting through sprawling ‘cities’ between air-conditioned buildings, could ever survive rapidly escalating oil prices once the global economy starts to recover. But maybe, with every building a micro power station storing energy with hydrogen fuel-cell technology that also powers cars, the future for such places is not as bleak as it once seemed. Maybe. Even so, there will be a painful transition period, protracted by the resistance of SIR corporations and the politicians they lobby and fund.

TIR will inevitably temper one of modernity’s most destructive features, the unchecked and irresponsibly exercised power of giant multi-national corporations: many see the curbing of the corporate system as a fundamental necessity if we are to progress to sustainability. This had its initial origins at the birth of modernity, with the issuance of royal charters in the early 15th century when the Portuguese king licensed the exploration of Africa. It took a further step towards their contemporary form considerably later when England and the Netherlands licensed their respective East India companies around the beginning of the 17th century. Besides initiating what we now know as globalisation, this issuance of charters was how the nobility retained power and profited from the rising mercantile class, and eventually led to the modern corporation as we know it.

A key feature of the chartered companies and today’s corporations is they distance shareholders from the source of their wealth, and even awareness of how it is created. Thus seemingly honourable people once lived in good conscience off colonialism and slavery, and now off the most rapacious of extractive industries destroying the planet. Hence discussion in some of the Greater London Authority’s documents about making London a sustainable city remains fatuous when the engine of its economy is the City of London (the banking and financial services sector).

Yet the corporate system and the big banks that are part of it are attracting calls for radical reform − among the less threatening of which is to factor in and pay for resolving externalities.

THE COMPUTER’S PLACE IN THE ‘ORGANIC UNIVERSE’

Far and away the most potent current agent of change is the computer. Initially this has supercharged the destructive impacts of the Second Industrial Revolution, not least by making it possible for vast sums of money to slosh instantly around the world with reckless disregard for local impacts or long-term consequences. At a more mundane level, the computer allows many of us to work from home.

This has consequences for the design of the home, as a live-work unit in contemporary parlance, and for the life of the neighbourhood, leading to the burgeoning number of coffee shops and other local meeting and socialising places for home-workers wanting company. It is the computer that will also bring about the TIR, seemingly our best chance for achieving sustainability and living in harmony with the regenerative cycles and capacities of the biosphere. So although the computer has already had an enormous impact on almost every aspect of our lives, it has still to affect us in many more ways. Its advent is of pivotal importance comparable with the birth of the industrial revolution, and some say of even greater significance.

| Newtonian Mechanical Universe | Living Organic Universe |

|---|---|

| Static and deterministic | Dynamic and evolving |

| Space and time both absolute and separates | Space and time are inseparable |

| Universe is the same for all observers wherever they are in space or time | Dependent on the observer |

| Consists of inert objects with simple locations. Organisms within space and time | Consists of de-localised and mutually entangled space |

| Space and time linear and homogeneous | Multi-dimensional space-time |

| Primary truth | Linear and heterogeneous |

| Local causation | Non-local causation |

| Non-participatory, excluded and impotent entanglement of observer | Creative and participatory |

| Observer | Observer and observed |

Every change discussed here has been powerfully influenced and even precipitated by the computer and the web of instantaneous communications it has facilitated. With internet access penetrating every corner of the globe, the web has provided Gaia with a nervous system so that each of us can be in touch with and informed about what is happening anywhere. Without the computer’s awesome number-crunching and simulation capacities we could not grasp the complexities of climate change nor design the built environment to ameliorate it. Indeed, every aspect of the design, engineering and construction of architecture has been radically affected by the computer. This has brought great benefits but also challenges to our understandings of the very purposes of architecture and how we relate to it. These will be explored in a later essay.

Science, and the technologies it spawns too, has also been radically transformed by the computer. Many natural processes were either much too slow or far too speedy to be accurately perceived, analysed and understood. These are now easily modelled on the computer, adjusting different variables until a model is created that behaves just like the natural system under study. Thus fields concerned with taxonomy now also study complex dynamic processes of emergence. Moreover, the computer is not limited to studying the simple, linear chains of cause and effect that characterise Newtonian science but can model complex, simultaneous and multi-directional interactions between many ongoing processes.

Although the shift had been going on since long before, the advent of the computer gave further impetus to one of the most profound paradigm shifts in science: Newton’s dead and mechanistic, clockwork universe is giving way to what is referred to as the Organic or Living Universe, which is understood to be alive, self-organising (autopoiesis), ever-evolving and constantly creative. (Some differences between the old Newtonian and the new Organic Universe are summarised in the table derived from one by evolution biologist Mae Won-Ho.) Science no longer only involves reductive analysis of isolated objects linked in simple causal chains but deals with multiple simultaneous interactions, with complex systems and the inter-relationships within and between them.

Moreover, we humans are no longer detached observers but, as implied in quantum mechanics, are to some degree integral participants in these systems and processes.

This huge shift is a major reason for 400 years of modernity being replaced by a new cultural paradigm underpinned by a radically different science. Youngsters educated in this new science will not only understand the world intellectually in another way to most people today but will also have a viscerally different experience of it, as participants rather than mere observers. This will in turn profoundly impact on how we want to live. We defended ourselves against a meaningless, dead universe by walling ourselves off with consumerist goodies and addictive distractions. But once we understand and sense the cosmos is alive we will want to disencumber to better embrace and engage with this ever-evolving being.

FINDING REAL MEANING IN HUMAN VALUES

Already before this change in our subjective experience of the world, another major agent of change is also subjective: this lies in human values, or perhaps not so much in changes in them but in an expectation of living in accord with one’s personal values. We increasingly recognise that real happiness and peace of mind cannot be achieved by betrayal or compromise of these values. A key step in many forms of psychotherapy and business consultation today is the elicitation of values, whether personal or corporate, and devising ways of living and acting in accord with them.

Throughout the course of history, until a generation or so ago, people tended to accept their station in life and only a privileged elite could live entirely as they wished. Now ever more people feel that they have a particular talent or purpose to realise. In some this manifests as an unrealistic sense of entitlement, but in the better adjusted and more mature this comes as an urge to contribute, to help others and the world, and thereby give their lives meaning and facilitate their realisation of their full potential.

This again has profound consequences for architecture and urban design, and the pursuit of sustainability. Ask probing questions of people about how ideally they believe we should live: What should be our relationship with neighbours and community? How should we travel to work and get our children to school (driving the latter every day, or walking along leafy, safe routes, say)? What should we eat and how should it be produced and sold? The more you probe, the more evident it becomes that people are often not living in accord with their values, and moreover that would be impossible in the contemporary city. How, for instance, might we achieve and combine no commuting, growing our own vegetables, recycling all waste locally, living in a diverse and mutually supportive community, and letting children run wild in safety while also bringing them up to be familiar with how we make our living?

‘SOCIETY AND ENVIRONMENT WILL BE SUSTAINABLE NOT LEAST BECAUSE CONCOMITANT CULTURES AND LIFESTYLES WILL OFFER THE PSYCHIC SATISFACTIONS OF A MEANINGFUL LIFE − RICH IN CONNECTIONS TO NATURE, PLACE AND COMMUNITY’

The impossibility of living in accord with our deep values and beliefs leads to an underlying, usually unacknowledged, malaise, from which we distract ourselves through excessive consumption and other forms of essentially addictive behaviour. All this has to be addressed in designing for sustainability. To radically revise our lifestyles, we must radically revise our human settlements, at the levels of the layout and functional mix of urban areas, as well as of the organisation and functional mix of individual buildings. We certainly cannot keep devouring the countryside with a sprawl of housing estates, which are wasteful in land and the time and energy spent commuting, nor constructing soulless urban areas conceived as mere aggregations of individual buildings rather than contiguous social fabric.

Other manifestations of changes in values are the many dimensions of the return of the feminine (after millennia of a dominating patriarchy), the rejection of racism and the advocacy of multiculturalism. Although these are forces for change, for moving beyond modernity, they are also consequences of it and postmodernity, some of their final and finest gifts.

ASSESSING THE SCALE OF THE CHANGE

In many periods of past and recent history, people were convinced that they were on the threshold of profound epochal change. This was certainly true of the 1960s, but also of other periods before and, for some people, since.

Yet the case then for people thinking themselves on such a brink was far less compelling than it is now, particularly because of the huge and accumulating impacts of the computer. The relevant questions seem to be less about whether we are undergoing epochal change, than in how major this change will be. And which epoch is drawing to a close? Or should that be epochs? And what will be the characteristics of the new era? That the age of heavily oil-dependent modern architecture will soon be over appears obvious. It seems similarly certain that while we will continue to use and preserve the infrastructure from the Second Industrial Revolution (which roughly correlates with the period now known as Modernism) and aspects of it will continue, making the transition to the Third Industrial Revolution will bring huge benefits and perhaps our best chance of collective survival. That modernity, the longer 400- to 500-year-old epoch, is passing also seems relatively uncontroversial. But with that and the quest for sustainability, are we not also seeing the end of the quest, which was already underway with the founding of the first cities some 8,000 years ago, to conquer nature? Now, instead of subduing it we must seek to live in symbiosis with nature, not least by applying the ecological understandings bequeathed by modernity.

Will we then reverse our progressively acquired sense of separateness − from nature and cosmos, from other people and community − a prime characteristic of Western consciousness that contemporary science considers fallacious? This seems to have started with the first Mesopotamian cities, partly as the consequence of the invention of scripts and linear, left-brained modes of thinking these induced (which repressed the feminine); and in Europe it began as warrior nomads swept in from the steppes to displace the worship of a fertile Mother Earth with vengeful sky gods. This sense of separation gained impetus as Greek philosophers stressed reason and dualism, to be intensified again through the rediscovery of reason in the Renaissance, the dualism of Descartes and the ideas of the Enlightenment.

For decades now, theories and discoveries in science have been telling us this sense of separateness is a delusion, as is the sense of reality that goes with it. This will eventually sink in, though many wonder why it is taking so long, so closing another long phase in our development. Probably all these phases of differing longevity in human, or at least Western, history are coming to an end more or less simultaneously. This powerfully highlights how momentous the transition is we are undergoing.

But to focus our explorations in the most manageable and fruitful way, next month we will discuss the transitions from pre-modernity to modernity, and then to postmodernity and how these were and are reflected in architecture − that is momentous and revealing enough. Although hers is not the framework we will be drawing on, let’s close with a table adapted from Charlene Spretnak’s brilliant book The Resurgence of the Real.

RESURGENCE OF THE REAL

| Modern | Deconstructionist Postmodern | Ecological Postmodern | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-narrative | Salvation and progress | None (They’re all power plays) | The cosmological unfolding |

| Truth mode | Objectivism | Extreme relativism | Experientialism |

| World | A collection of objects | An aggregate of fragments | A community of subjects |

| Reality | Fixed order | Social construction | Fragmented |

| Sense of self | Socially engineered | Fragmented | Processual |

| Primary truth | The universal | The particular | The particular-in-context |

| Grounding | Mechanistic universe | None (total groundlessness) | Cosmological processes |

| Nature | Nature as opponent | Nature as wronged object | Nature as subject |

| Body | Control over the body | ‘Erasure of the body’ (It’s all social construction) | Trust in the body |

| Science | Reductionist | It’s only a narrative! | Complexity |

| Economics | Corporate | Post-capitalist | Community-based |

| Political focus | Nation-state | The local | A Community of communities of communities |

| Sense of the divine | God the Father | ‘Gesturing towards the sublime’ | Creativity in the cosmos, ultimate mystery |

| Key metaphors | Mechanics and law | Economics (‘libidinal economy’) and signs/coding | Ecology |

Here she contrasts three paradigms − or as she prefers, ‘cultural ecologies’ − Modernity, Deconstructionist Postmodernism (the transitory, hyper-relativist mode of thought usually referred to as Postmodernism) and Ecological Postmodernism, which she implies is the emerging long-term successor to modernity. Her vision of Ecological Postmodernism is consistent with new and emerging understandings from science and incorporates new visions of what it means to be fully human.

Based on a living and unfolding cosmos, its understanding of reality is more dynamic, relational, complete and complex than that of modernity, strongly contrasting with both the ‘objective’, fixed order of modern reality and the arbitrary social construction of that of Deconstructionist Postmodernism. The table may not be exactly self-explanatory, especially without the supporting argument of the book, but even by itself is richly suggestive and worthy of contemplation in preparation for next month’s explorations.